Current Research Interests

My planetary chemistry research involves modeling physical and chemical processes in planetary and astrophysical environments. The goal of this work is to better understand the underlying chemistry responsible for the observed properties of planetary atmospheres, and to provide clues about the formation and evolution of planetary systems. A current list of publications is available here.

Ongoing research projects are divided into two general themes:

The first major research theme involves a comprehensive study of chemistry in the atmospheres giant planets (Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, Neptune), exoplanets (planets orbiting stars other than the Sun), and brown dwarfs (objects with insufficient mass to sustain hydrogen fusion).

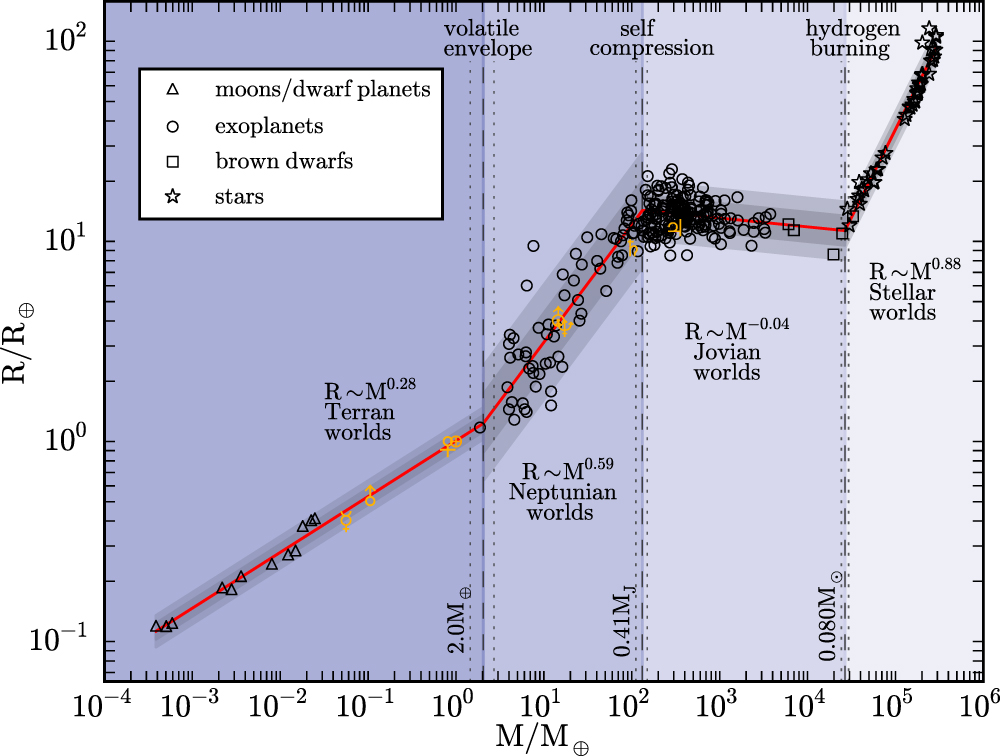

Figure: Mass-radius plot (normalized to Earth = 1) for objects from dwarf planets to low-mass stars. Brown dwarfs (~10-80 Jupiter masses; covering the right half of the "Jovian worlds" category in the plot above) can be thought of as the lowest-mass products of star formation. Figure from Chen & Kipping (2016).

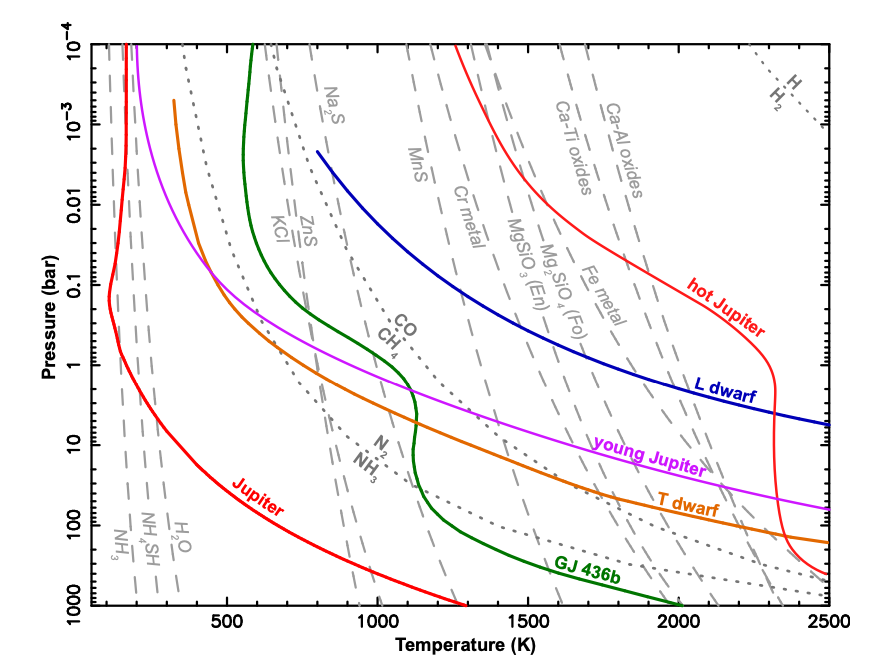

This work includes modeling reaction chemistry and cloud formation (including exotic clouds consisting of rocky material or metals) in hydrogen-dominated planetary atmospheres, and exploring potential effects on observational properties.

Figure: A summary of atmospheric chemistry in hydrogen dominated atmospheres. Colored curves are thermal profiles of various objects, from Jupiter to warm brown dwarfs and hot exoplanets. Dashed lines are the condensation curves for cloud-forming species in a solar-composition gas; dotted lines indicate equal abundance curves for major molecular species in the gas phase.

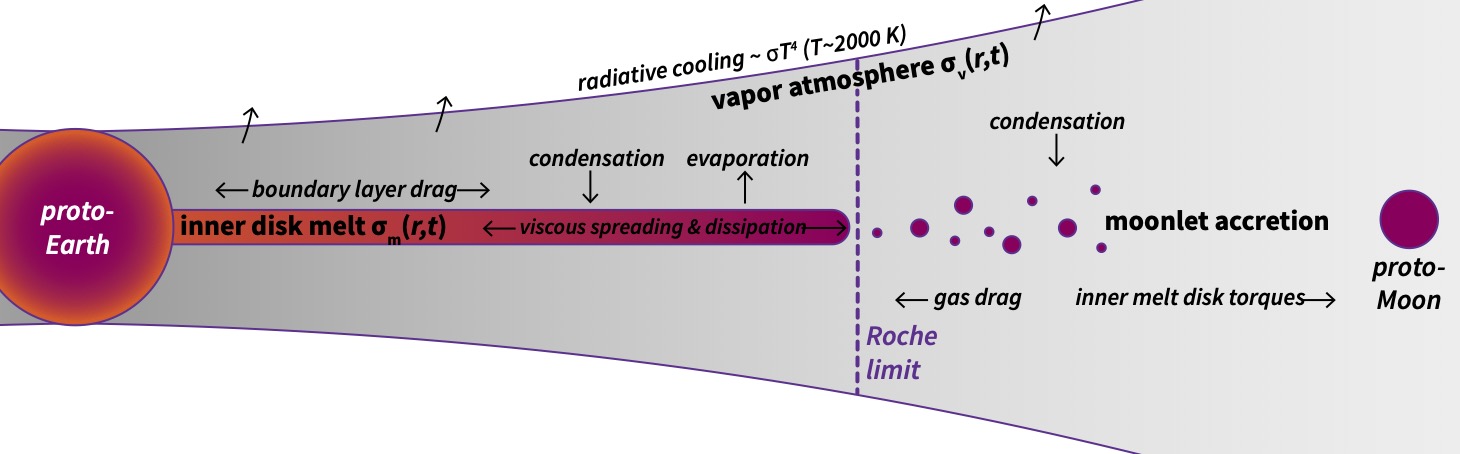

The second major research theme involves an exploration of the chemistry of the forming Moon. In the prevailing hypothesis for lunar origin, the Moon formed from an Earth-orbiting disk of rocky debris that was produced by the collision of a large planet with the Earth early in its history (the "giant-impact hypothesis").

Figure: Schematic of the protolunar disk: an Earth-orbiting disk of rocky debris following the giant impact event. In this scenario, moonlets produced at the outer edge of the melt disk gather onto the forming proto-Moon. The lunar material accreted in this way will be shaped by chemical processes taking place in the two-phase disk.

Understanding the physical and chemical processes that may have affected the resulting high-temperature (molten rock + vapor) debris disk is important for understanding the inherited chemical abundance patterns observed in lunar samples (provided by meteorites and the Apollo missions), and may provide further clues about the origin and evolution of the Moon.