The development of comprehensive model frameworks to explain observed phenomena - a key component in Kuhn’s idea of paradigm formation - can be illustrated with something like the following.

This comes out of Thomas Kuhn's landmark The Structure of Scientific Revolutions

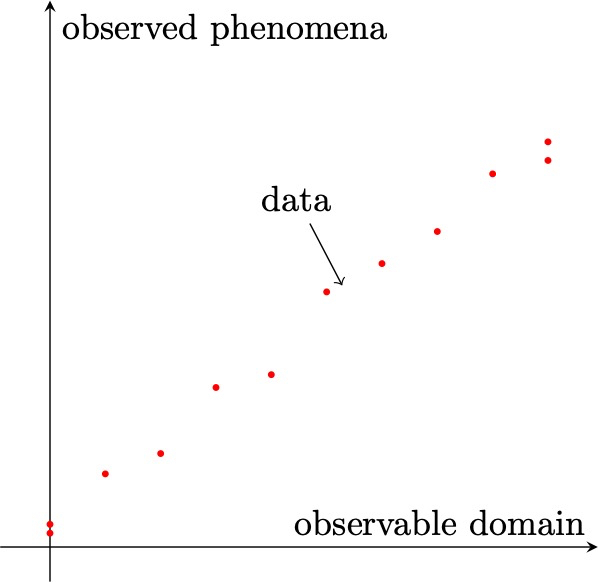

Suppose we explore and collect numerous pieces of evidence within some field of study – from the distribution of fossils in rock strata, to the temperature of stellar photospheres, to the inhibition of proteins on a viral membrane – and (within their respective domains) try to piece these various phenomena in some sort of systematic way:

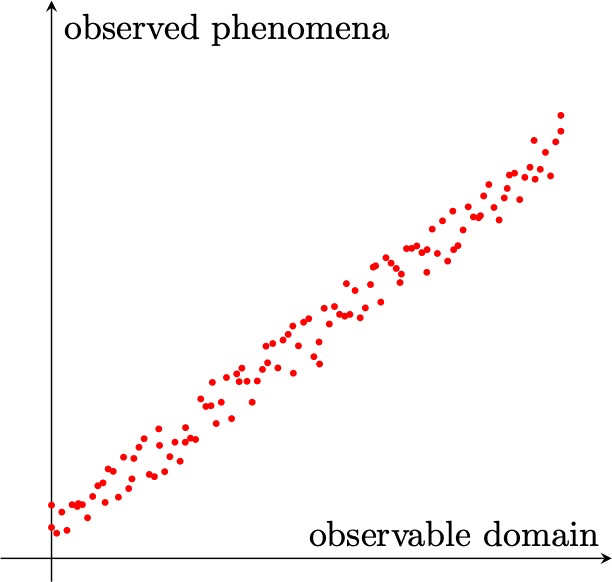

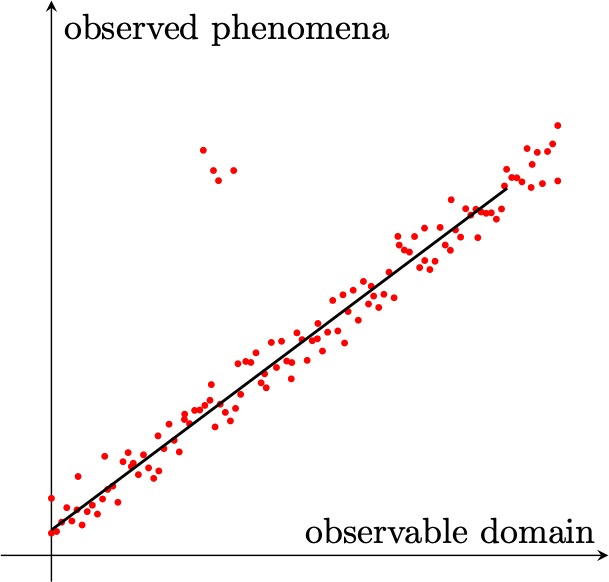

Doing so, suppose we begin to see a pattern emerge. This is exciting because it suggests that we're working our way toward identifying some underlying relationship that ties the evidence together. Over time we find that additional measurements and observations reveal a clear pattern:

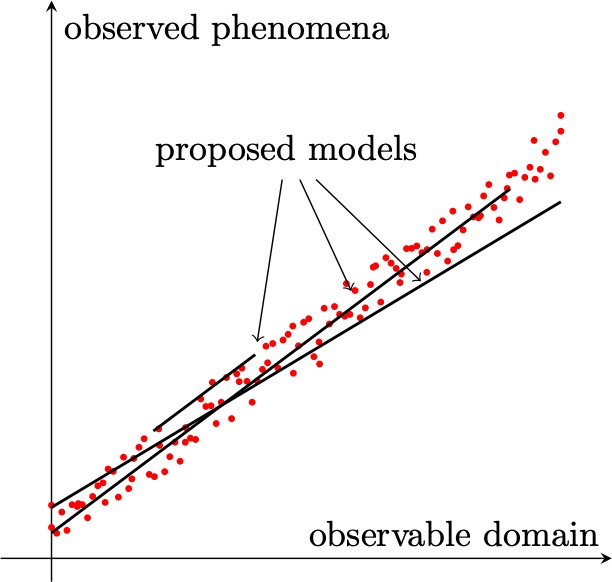

With a clear pattern established, we will begin seeing attempts at the development of models -- or more broadly, any explanatory framework -- that explains some or all of the available evidence, and how it all fits together.

The comprehensive model that does appears to do the best job of explaining all of the available evidence in a self-consistent framework will tend to be adopted as the paradigm for understanding the observed behavior.

At this point, something Kuhn calls normal science will tend to dominate: new experiments or observations will begin with the assumption that the paradigm is valid. Moreover, scientific activity will largely explore how new data and evidence might fit within the existing framework.

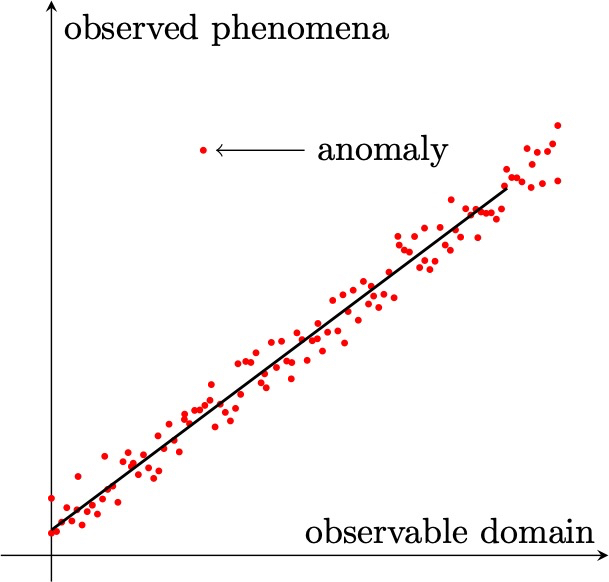

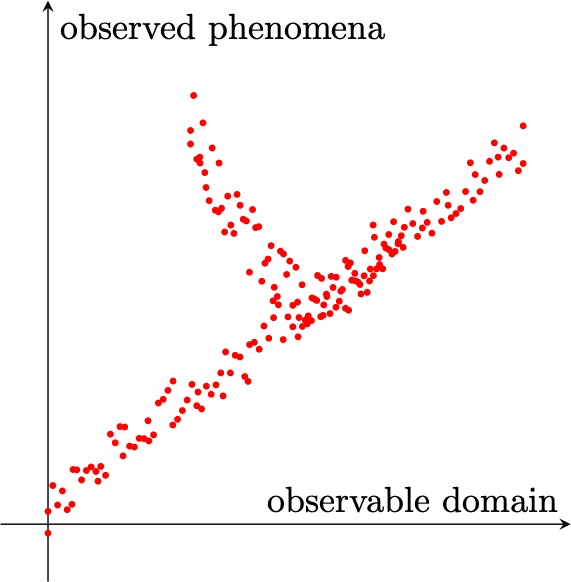

But now suppose a research group provides some new evidence: a new planet is found, or a new isotope measurement is done for a meteorite sample, or a novel cellular pathway is discovered, or an experiment is conducted under a particular set of conditions that yields unexpected results: any of which might yield data that is not consistent with the model paradigm:

As Kuhn notes, paradigms are highly sensitive to anomaly and they tend to stand out. By itself however, an anomaly is not enough to make us reject our existing model paradigm. After all, the model still does a really good job of explaining nearly all of the available evidence, and there is always the possibility that the anomaly is a result of scientific error.

Different research groups (including rivals) will try to reproduce the anomaly and/or seek explanations for its appearance. Following "normal science", however, attempts will first be made to incorporate the anomaly within the existing paradigm, if possible. So what happens at this stage is important...

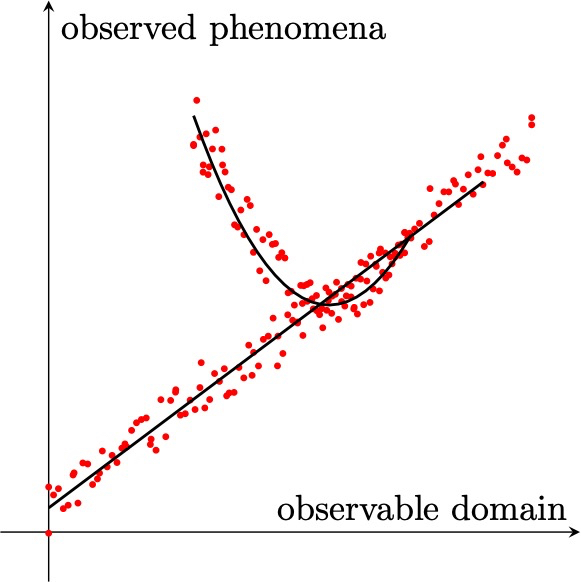

Now things have gotten interesting - it looks like the anomaly could be real! Efforts will intensify to explore and characterize the anomalous behavior. There will be a growing recognition that the favored model paradigm is not fully comprehensive. However, the model paradigm will not be discarded until a new model can be formulated that explains both the old and new data. Over time, a new picture of the available evidence may emerge:

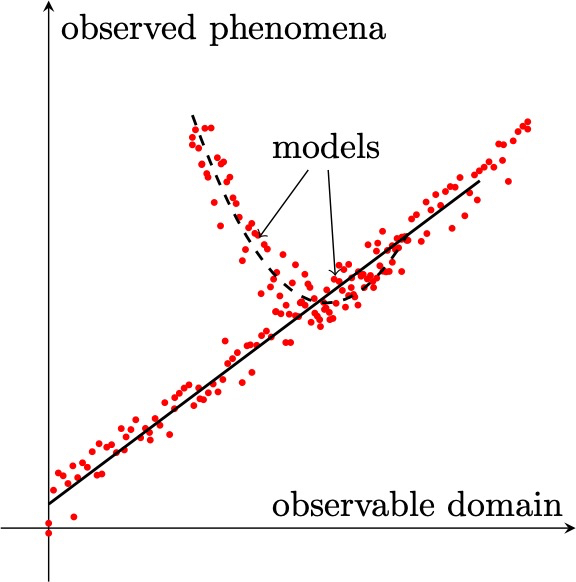

Numerous attempts will now be made to construct -- or combine -- models that can explain all of the data. It is not uncommon for different models to be combined to explain different lines of evidence. For example, in one scenario we might retain the original model alongside a new model (indicated by the dashed curve) that can explain the more recently discovered phenomena:

Again it is important to note that both models may be retained -- even as we recognize that they are incomplete -- because of their continued ability to explain and predict for a subset of observational data.

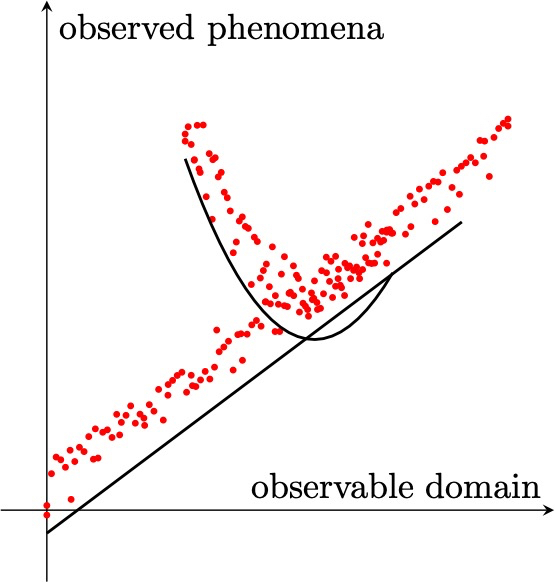

However, if both models are retained, the apparent limitations of each model will provide powerful incentive to develop and/or discover a new explanatory paradigm that can connect all of the evidence into a single framework. It's possible that this won't be implemented all at once. For example, suppose a we find an underlying relationship that appears to explain the overall observational trends but doesn't quite explain individual pieces of evidence:

This too, would strongly suggest that we are on the right track toward a new explanatory framework, and it is very likely that such a model paradigm would be at least provisionally accepted. At this stage, more and more of the community may begin adopting the new model, and/or exploring ways how it might be modified and improved upon until it is able to explain the evidence, whereupon a new paradigm will emerge:

This is the prevailing paradigm for normal science - at least until a new anomaly emerges! Nevertheless, in Kuhn's definition, scientific paradigms are explanatory, testable, and predictive, and they provide valid and meaningful frameworks for interpreting and understanding observations of the world around us.

back to the beginning